August 18, 1955 is a day that will live in infamy for people of the Northeast. That was the day the Flood of ’55 ravaged our small town. Back-to-back hurricanes Connie and Diane turned peaceful creeks into raging torrents, sweeping aside towns from Pennsylvania to Connecticut and killing hundreds, seemingly in the blink of an eye.

As a child, I don’t remember much of that time, but years later, as a journalist investigating the events of that terrible night, I was stunned by the hardship and heroism of those who survived. With the benefit of hindsight, I decided to explore their stories through a series of novels.

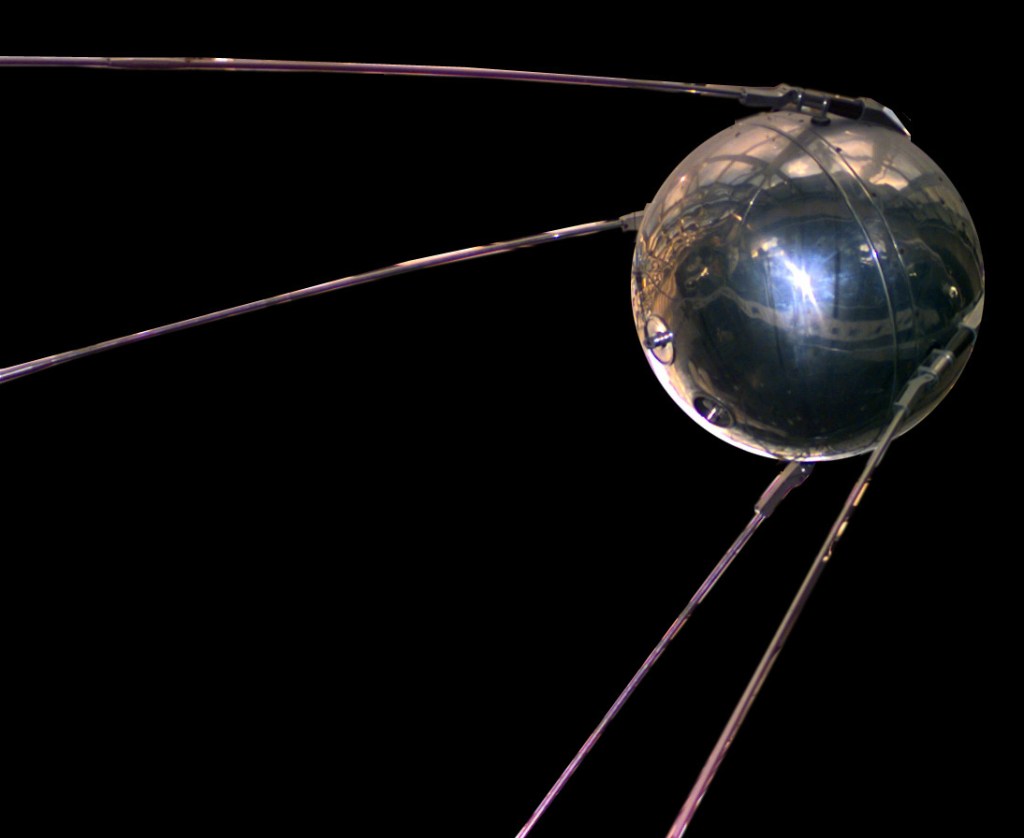

The first book in the trilogy, Distant Early Warning, introduces us to the Andersen family as they struggle to recover from the devastating flood. The novel, and the ones to follow—Cold Fire and Good People—portray the dreams and fears of a family, town, and country as they navigate the promise and perils of Cold War America. Distant Early Warning doesn’t only refer to the DEW Line, the system of Arctic radar stations designed to detect incoming Soviet bombers. The title serves as a metaphor for the internal system that warns us of impending danger, warnings we often ignore.

Russia, rockets, race, and repression—issues the Andersens tried to resolve in the ’50 that revisit us today. As does their struggle for mercy and hope.

Theirs is a journey from darkness to light. Follow it here. Or start with that terrible night of August 18 in this excerpt from Chapter 4.

AT TEN TO NINE, Georgia let Skippy out for a short walk, wiped the dog’s back with a dishtowel, and moved her box into the kitchen. This was Georgia’s time. Switching on the television, she settled on the couch and tried to watch Fear Strikes Out, a movie Marsh would have liked about center fielder Jimmy Piersall. But at 9:30 the lights vanished with a snap. Suddenly blind, she groped toward the telephone. It was out, too. Now there was no way to call Marsh, even if she knew where to find him. And he had taken the car.

From the street, shouts competed with the swish of tires, then a shudder as something heavy struck the bridge, rattling the house as if the earth had broken in two. The room squeezed her heart. Inhaling through her mouth, she told herself she was responsible for the children and had to think of their welfare. Marsh said that, if the town declared an emergency, the fire chief would blow the siren, and someone would come to their rescue. She could wait for the siren, but not in this stifling dark.

Groping through a drawer in the kitchen, she found a small flashlight, thumbed the button and, checking that Skippy was safe in her makeshift bed, traced a path upstairs. Awakened by a noise in the street, Wil emerged from his room, still dressed in his life vest and rocket pack, ready to battle whoever he imagined had attacked the house. Cradling Penny—the baby fussed but didn’t cry, the cereal settling for once—Georgia led him downstairs, where she rummaged through another drawer to find their good tapers and a box of matches. Placing the candles on the table, she opened the screen door and peered into the dark. She didn’t need a light to sense the rush of water across their yard. The town’s storm sewers were designed to handle a hard rain. Their home was not.

Wil noticed it first. Lifting a hand to stay his questions, she listened to the tinny sound of water trickling into the house. Opening the door to the basement, she played the flashlight over a small lake, the surface foaming like root beer. The seasonal items they’d stored bumped against the bottom of the steps—boxes of clothing, Christmas decorations, a pair of lawn chairs Marsh had promised to fix. Within the time it took to identify each object, the water rose to the second step, then the third. In minutes, it would reach the kitchen, sweeping them and their possessions through the front door.

The playpen sat a good nine inches above the living room floor. She set Penny inside and turned to her son.

“You’re a big boy now. I need you to help Mommy move some things upstairs.”

Slipping into her boots, assuring herself that Wil had buckled his, she tottered down the basement stairs, hanging onto the railing, calling for Wil to be careful. The water had risen so rapidly, she had to duck to see under the rafters. Playing the light over the walls, she watched as water gushed between the stones, flooding the furnace and coal bin and inching dangerously close to the fuse box. They’d used the last of their spares, and there was no way, once the power came back, she was going to wade through that water and use a penny to complete the circuit.

Urging Wil up the stairs, she closed the door and leaned her head against it. Even with the curtains open, the windows appeared blank, the streetlamps dead. The flashlight cast a narrow cone in one direction only. There was no place to set it and see clearly enough to climb the stairs to the bedrooms. Georgia would have to hold the light and the furniture, and her hands were already slick with sweat. She and Wil were able to lift the lamps, books, and ottoman onto the dining room table. The rugs they lugged upstairs and piled into the bathtub. There would be a mess to clean before she could bathe Penny, but it was the best they could do.

Wil hovered at her side, jittering as if he had to go to the bathroom. “Can we bring Phil upstairs?”

Marsh had spoken to Wil about how, as people grew older, they said goodbye to their imaginary friends, but now was not the time for a sermon. Besides, the Philco had cost nearly five hundred dollars, more than a tenth of what Marsh earned at the paper, and Georgia wasn’t about to lose it. She and Wil tried to drag the television up the narrow stairwell but couldn’t shove it past the first few steps. They left it on the landing and made their way to the kitchen.

Where was Marsh, and was he all right? And where were the firemen he was supposed to send? Wil’s bedtime prayer rang in her head.

Now I lay me down to sleep.

The radio had died. Rain thrummed against the roof, the sound clotting her ears. She considered leaving, but where could they go on foot? Besides, there was a house between them and the creek and a concrete retaining wall lining one side of the bank. The town must have thought it would hold the water or they wouldn’t have built it.

I pray the Lord my soul to keep.

Thunder rolled over the house, rattled the windows, shook the floor. Wil took her hand. Penny issued a startled cry. Lifting her from the playpen, Georgia moved to heat water for a bottle before she realized the appliances were as dead as the lights. Dumb, she thought and dutifully pushed a nipple through its plastic ring, mixed the formula with tepid water from the tap, and let it sit.

If I should die before I ’wake.

The fire sirens came on with the whoosh of a gas burner, the sound oscillating between panic and fear. It cut through her chest. The creek would ignore the warning. Georgia pictured it as a mythic creature rising on stout legs, beat its chest, thundering its demands. She, too, would not be moved. They would ride out the storm until help arrived.

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

The sound of rain intensified. It seemed to buckle the walls. Holding Penny and the flashlight, she instructed Wil to jam towels under the back door. That would keep some of the water at bay. The basement posed the real threat. The old stone walls could collapse. Before sealing the cellar, she ventured a last look. Clasping the light to the baby’s back, Georgia aimed at the door. With her free hand, she reached for the knob and hesitated, her fingers suspended in the beam, her body sensing the weight of something trapped below the stairs, the pressure on a dam ready to burst. As if watching herself, she grasped the handle and cracked the door.

Even as she stumbled back, she knew she’d made a terrible mistake.