August 15, 1969, capstone of a tumultuous decade. Life in the rural town of Pennsboro, Pa. is about to explode. A dam that would flood the valley pits family against family. Marchers riot. Buildings burn. Amid the chaos, two lovers risk everything to fight for their home—and a chance to command the stage at a rock festival in a farmer’s field in New York State, an event we now know as Woodstock.

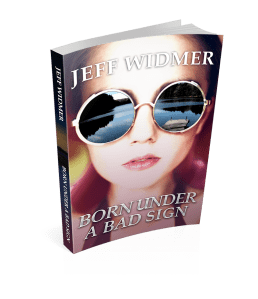

I grew up in those times, in the shadow of an unpopular dam, the government’s eviction of squatters, surrounded by the sounds of peace, love, and revolution. To understand the contradiction, I wrote a novel about those two kids. The result was Born under a Bad Sign, a dramatic and nuanced portrait of love and loss in the Sixties.

It begins, as many of our stories do, with a crush. Elizabeth Reed loves photography, the river the government wants to dam, and a musician who refuses to commit. Hayden Quinn, the guitarist Rolling Stone calls the next Jimi Hendrix, feeds another obsession—to play the biggest concert of his life. He presents Elizabeth with a dilemma: stay to save her family’s farm, or follow him into the unknown.

With saboteurs targeting everyone she loves, Elizabeth faces the greatest risk of all—whether to trust her head or her heart.

You can read the full story of their struggles here. Or start with Chapter 1 and the night the world fell away.

1.

FROM BEYOND THE HILLS came a jagged flash of light. Elizabeth Reed counted five seconds before the sound rumbled across the infield of the raceway, this makeshift venue for the largest outdoor rock concert on the East Coast. Another flash, and another ripple of thunder. In an improvised call and response, the crowd echoed its approval. The tower that held the lights and PA system trembled. So did Elizabeth’s arms and legs. She let the dizziness pass and, willing her stomach to settle, tucked both cameras under her arms and climbed to the sky.

The warm-up band had just finished, the announcer promising that Orwell, fresh off its national tour, would soon take the stage. A wall of people surged forward. Despite the scalding July heat, this was the group’s homecoming and the locals had turned out in force, thousands of ragged kids with beards and muumuus, jostling each other in a fog of beer and smoke. Two years after Monterey Pop and the festival had come of age. So had the band.

The tower swayed enough to cause Elizabeth to question her bravado. Despite the knot in her stomach, she climbed past speakers and spotlights for a better view of the makeshift stage, a plywood floor laid across a half-dozen flatbed trailers. The platform had been hastily constructed for the festival, the biggest in Pennsylvania’s Minisink Valley and a warm-up for one she’d heard could be even bigger, next month’s Woodstock Music & Art Fair in nearby New York.

That was the real object of the evening’s performance, a final rehearsal for Orwell and its leader, Hayden Quinn, the guitarist Rolling Stone had called the next Jimi Hendrix, the man that Elizabeth, fresh out of high school, had followed halfway across the country as the band’s unofficial photographer. It was make or break time for the group. The band’s manager, Elizabeth’s Uncle Morey, had invited the man organizing Woodstock, Michael Lang, to attend the concert. So far, she hadn’t seen anyone fitting Lang’s description.

As the wind rose to meet the night, Elizabeth realized that, if the crowd pressed closer, the tower could tip. Since her dizziness disappeared if she didn’t look down, she focused on the distance, tracking the Delaware as it wandered between Pennsylvania and New Jersey like a nomad, flowing freely despite the government’s effort to dam the river and drown her family’s farm. With the telephoto lens, she could isolate her property, snug in the rich bottomland of the valley. Camera in hand, river and fields spread below, she felt exhausted, scared, and ridiculously happy.

Voices below startled her. Dressed in black, two members of the security crew waved her from the tower. The yelling morphed into the sound of hammering. Against the raw wood of the stage, Tommy Reed nailed cardboard cylinders to rows of two-by-tens, preparing the fireworks for the evening’s finale. He seemed dwarfed by the munitions.

When the sound system kicked in with a recording of “Crossroads,” Elizabeth gripped the metal pipes to maintain her balance. Despite the rush of adrenaline, her arms ached from lugging the heavy Nikons all day. With a normal lens, the weight seemed bearable. But when loaded with a zoom and a motor drive, the outfit felt as if it weighed as much as a bale of hay. Before she descended, she snapped a picture of Tommy as he wired his makeshift rig, the camera hot and slippery in her hands. Heaven help them if she dropped it on his head.

As soon as she landed, the security officers assumed their positions in front of the stage while the roadies assembled the last of the equipment. Her older brother Robbie frowned as he arranged cymbals and tightened the drumheads, his rusty hair in a deliberately unhip buzzcut. Reaching above his head, Cordell White plugged his bass into a stack of amplifiers and plucked a few notes. Unlike Robbie, who wore his usual white T-shirt and shorts, Del had dressed for show in leather pants, a jacket of purple satin, and a high-crowned Navajo hat with a yellow plume. Both of them looked frustrated, or mad.

Tommy caught her eye and jerked his head toward the edge of the stage. He, too, appeared angry, a look that was highlighted by chapped lips, hair the color of licorice, and a nose as sharp as a chisel. The only festive thing about him was the tie-dyed headband.

“Hey, Cuz,” she said, drawing a face that signaled either irritation or fatigue.

He smelled of oil and mint. As usual, he wore sunglasses so dark that she wondered how he could see to connect the fireworks. Pecking him on the cheek, she took in the rows of rockets, mortars, and Roman candles that crowded both sides of the stage and felt a twinge of concern. “Aren’t they a little close?”

Tommy scratched his back with a screwdriver. “Close?”

“To the band.”

Another crack of thunder and Tommy dragged a tarp over the pods. “Wait and see.”

As security stopped a ginger-haired man flashing press credentials, Elizabeth regained the tower. One by one, the members of Orwell wandered onto the stage to a cascade of applause. Robbie positioned his cymbals, Del and Quinn hunched over tuning pegs, and Mattie, jiggling her ample ass, asked the crowd how they were doing. As the band struck its first tectonic chord, the audience thundered their approval.

Mattie belted out the first number with a ferocity that shook the towers, all trace of her Southern accent lost in the ricochet of sound. Robbie thrashed as if he were drowning in one of the cow ponds on the family farm. Even Del, who usually bobbed in place, stalked the boards, his face a darkening cloud.

Quinn followed with a scorching lead that featured a collision of Bach, Thelonious Monk, and Hendrix. Shirtless now and barefoot, he played with a single-mindedness akin to religious devotion, prowling the stage, slashing his guitar, bending strings until they threatened to snap. He hammered the neck with both hands as if playing a piano, the sound a frenetic cross between Paganini and Robert Johnson, the shaman who’d sold his soul to the devil for his talent.

From her perch, she tracked the band, feeling more than hearing the smack of the mirror as it lifted to admit the light, the whir of the motor drive as it advanced the frames. Pace yourself, she thought, or you’ll run out of film.

Like a tsunami, the intensity of the music grew, Quinn hurtling his body into the wave of sound, his head bowed, shoulders hunched, fingers on fire. Dreadlocks flew as he reared, face twisted in ecstasy, the notes tracking across his lips. No matter how many times she’d seen the show, Elizabeth felt stunned, and not just by the acoustical acrobatics. With the flick of his fingers, Quinn guided the music from brave too anxious to calm. Elizabeth felt warmth and humor, sadness and pity, and so much in between. It astonished her that anyone could convey such emotion without the use of a single word.

The band continued the pace, blazing through songs as if racing to an uncertain end. By the close of the set, their faces shone with euphoria and sweat. Robbie raised his sticks, caught the eye of Quinn and Del, and they miraculously finished on the same beat, even as Tommy launched the first volley of fireworks, burning the night in a shower of red and gold.

The musicians filtered off stage, waited a beat, and returned to a swelling ovation. With a deep bow, and a nod from Mattie, they launched into one of the medleys Quinn had arranged as an encore. Even before Elizabeth traced their faces through the telephoto, she could tell that, as the music grew more frantic, they struggled to hear. Hitting the final chorus, Mattie looked over her shoulder as if she were lost in the woods. Robbie buried his head in his drum kit. Del and Quinn traded places, Del moving to the monitors along the wing while Quinn arched over the stage to listen to the PA speakers.

The music had grown so loud that Elizabeth could barely feel the vibration through the camera body as the motor drive cranked through another roll of film, thirty-six exposures in a matter of seconds before she hunched to reload.

This time, the band didn’t leave the stage. They bowed slightly, as if they’d expended so much energy they had little left for movement, before launching into the second encore, a reprise of their single, “Bomb Babies,” that ended in a cataclysmic version of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. Quinn had shortened the piece for maximum impact and, when he nodded, Tommy let loose with his final volley.

From the corner of the viewfinder, Elizabeth watched the skyrockets arc into the night and explode in phosphorescent swirls. She grabbed a shot of Tommy, who timed the bursts to coincide with the downbeat. As the encore hit its crescendo, he quickened the pace, unleashing a white-hot assault that mimicked the original cannon fire. The band fed off the energy, Quinn and Robbie flailing, Del leaning dangerously close to the fireworks while Mattie spread her arms to embrace the crowd.

Then, as Elizabeth lifted the camera to her face, the stage flashed with a blinding light and the world exploded.